|

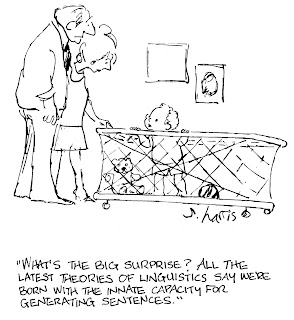

© Cartoonstock.com

|

Noam Chomsky is widely regarded as an intellectual giant, responsible for a revolution in how people think about language.

In a recent book by Chomsky and James McGilvray,

the Science of Language, the foreword

states: It is particularly important to understand Chomskys views

not only because he virtually created the modern science of language by himself

. but because of what he and colleagues have discovered about language particularly in recent years

As someone who works on child language disorders, I have tried many times to read Chomsky in order to appreciate the insights that he is so often credited with. I regret to say that, over the years, I have come to the conclusion that, far from enhancing our understanding of language acquisition, his ideas have led to stagnation, as linguists have gone through increasingly uncomfortable contortions to relate facts about childrens language to his theories. The problem is that the theories are derived from a consideration of adult language, and take no account of the process of development. There is a fundamental problem with an essential premise about what is learned that has led to years of confusion and sterile theorising.

Let us start with Chomskys famous sentence "Colourless green ideas sleep furiously". This was used to demonstrate independence of syntax and semantics: we can judge that this sentence is syntactically well-formed even though it makes no sense. From this, it was a small step to conclude that language acquisition involves deriving abstract syntactic rules that determine well-formedness, without any reliance on meaning. The mistake here was to assume that an educated adult's ability to judge syntactic well-formedness in isolation has anything to do with how that ability was acquired in childhood. Already in the 1980s, those who actually studied language development found that children used a wide variety of cues, including syntactic, semantic, and prosodic information, to learn language structure (Bates & MacWhinney, 1989). Indeed, Dabrowska (2010) subsequently showed that agreement on well-formedness of complex sentences was far from universal in adults.

Because he assumed that children were learning abstract syntactic rules from the outset, Chomsky encountered a serious problem. Language, defined this way, was not learnable by any usual learning system: this could be shown by formal proof from mathematical learning theory. The logical problem is that such learning is too unconstrained: any grammatical string of elements is compatible with a wide range of underlying rule systems. The learning becomes a bit easier if children are given negative evidence (i.e., the learner is explicitly told which rules are not correct), but (a) this doesnt really happen and (b) even if it did, arrival at the correct solution is not feasible without some prior knowledge of the kinds of rules that are allowable. In an oft-quoted sentence, Chomsky (1965) wrote: "A consideration of the character of the grammar that is acquired, the degenerate quality and narrowly limited extent of the available data, the striking uniformity of the resulting grammars, and their independence of intelligence, motivation and emotion state, over wide ranges of variation, leave little hope that much of the structure of the language can be learned by an organism initially uninformed as to its general character." (p. 58) (my italics).

So we were led to the inevitable, if surprising, conclusion that if grammatical structure cannot be learned, it must be innate. But different languages have different grammars. So whatever is innate has to be highly abstract a Universal Grammar. And the problem is then to explain how children get from this abstract knowledge to the specific language they are learning. The field became encumbered by creative but highly implausible theories, most notably the parameter-setting account, which conceptualised language acquisition as a process of "setting a switch" for a number of innately-determined parameters (Hyams, 1986). Evidence, though, that childrens grammars actually changed in discrete steps, as each parameter became set, was lacking. Reality was much messier.

Viewed from a contemporary perspective, Chomskys concerns about the unlearnability of language seem at best rather dated and at worst misguided. There are two key features in current developmental psycholinguistics that were lacking from Chomskys account, both concerning the question of what is learned. First, there is the question of the units of acquisition: for Chomsky, grammar is based on abstract linguistic units such as nouns and verbs, and it was assumed that children operated with these categories. Over the past 15 years, direct evidence has emerged to indicate that children don't start out with awareness of underlying grammatical structure; early learning is word-based, and patterning in the input at the level of abstract elements is something children become aware of as their knowledge increases (Tomasello, 2000).

Second, Chomsky viewed grammar as a rule-based system that determined allowable sequences of elements. But peoples linguistic knowledge is probabilistic, not deterministic. And there is now a large body of research showing how such probabilistic knowledge can be learned from sequential inputs, by a process of statistical learning. To take a very simple example, if repeatedly presented with a sequence such as ABCABADDCABDAB, a learner will start to be aware of dependencies in the input, i.e. B usually follows A, even if there are some counter-examples. Other types of sequence such as AcB can be learned, where c is an element that can vary (see Hsu & Bishop, 2010, for a brief account). Regularly encountered sequences will then form higher-level units. At the time Chomsky was first writing, learning theories were more concerned with forming of simple associations, either between paired stimuli, or between instrumental acts and outcomes. These theories were not able to account for learning of the complex structure of natural language. However, once language researchers started to think in terms of statistical learning, this led to a reconceptualisation of what was learned, and many of the conceptual challenges noted by Chomsky simply fell away.

Current statistical learning accounts allow us to move ahead and to study the process of language learning. Instead of assuming that children start with knowledge of linguistic categories, categories are abstracted from statistical regularities in the input (see Special Issue 03, Journal of Child Language 2010, vol 37). The units of analysis thus change as the child develops expertise. And, consistent with the earlier writings of Bates and MacWhinney (1989), children's language is facilitated by the presence of correlated cues in the input, e.g., prosodic and phonological cues in combination with semantic context. In sharp contrast to the idea that syntax is learned by a separate modular system divorced from other information, recent research emphasises that the young language learner uses different sources of information together. Modularity emerges as development proceeds.

A statistical learning account does not, however, entail treating the child as a blank slate. Developmental psychology has for many years focused on constraints on learning: biases that lead the child to attend to particular features of the environment, or to process these in a particular way. Such constraints will affect how language input is processed, but they are a long way from the notion of a Universal Grammar. And such constraints are not specific to language: they influence, for instance, our ability to perceive human faces, or to group objects perceptually.

It would be rash to assume that all the problems of language acquisition can be solved by adopting a statistical learning approach. And there are still big questions, identified by Chomsky and others Why dont other species have syntax? How did language evolve? Is linguistic ability distinct from general intelligence? But we now have a theoretical perspective that makes sense in terms of what we know about cognitive development and neuropsychology, that has general applicability to many different aspects of language acquisition, which forges links between language acquisition and other types of learning, and leads to testable predictions. The beauty of this approach is that it is amenable both to experimental test and to simulations of learning, so we can identify the kinds of cues children rely on, and the categories that they learn to operate with.

So how does Chomsky respond to this body of work? To find out, I decided to take a look at The Science of Language, which based on transcripts of conversations between Chomsky and James McGilvray between 2004 and 2009. It was encouraging to see from the preface that the book is intended for a general audience and Professor Chomskys contributions to the interview can be understood by all.

Well, as one of the most influential thinkers of our time, Chomsky fell far short of expectation. Statistical learning and connectionism were not given serious consideration, but were rapidly dismissed as versions of behaviourism that cant possibly explain language acquisition. As noted

by Pullum elsewhere, Chomsky derides Bayesian learning approaches as useless and at one point claimed that statistical analysis of sequences of elements to find morpheme boundaries just cant work (cf. Romberg & Saffran, 2010). He seemed stuck with his critique of Skinnerian learning and ignorant of how things had changed.

I became interested in not just what Chomsky said, but how he said it. Im afraid that despite the reassurances in the foreword, I had enormous difficulty getting through this book. When I read a difficult text, I usually take notes to summarise the main points. When I tried that with the Science of Language, I got nowhere because there seemed no coherent structure. Occasionally an interesting gobbet of information bobbed up from the sea of verbiage, but it did not seem part of a consecutive argument. The style is so discursive that its impossible to précis. His rhetorical approach seemed the antithesis of a scientific argument. He made sweeping statements and relied heavily on anecdote.

A stylistic device commonly used by Chomsky is to set up a dichotomy between his position and an alternative, then represent the alternative in a way that makes it preposterous. For instance, his rationalist perspective on language acquisition, which presupposes innate grammar, is contrasted with an empiricist position in which Language tends to be seen as a human invention, an institution to which the young are inducted by subjecting them to training procedures. Since we all know that children learn language without explicit instruction, this parody of the empiricist position has to be wrong.

Overall, this book was a disappointment: one came away with a sense that a lot of clever stuff had been talked about, and much had been confidently asserted, but there was no engagement with any opposing point of view just disparagement.

And as Geoffrey Pullum concluded, in a review in the

Times Higher Education, there was, alas, no science to be seen.

References

Bates, E., & MacWhinney, B. (1989). Functionalism and the competition model. In B. MacWhinney & E. Bates (Eds.),

The crosslinguistic study of sentence processing (pp. 3-73). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available from:

http://psyling.psy.cmu.edu/papers/bib.htmlChomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N., & McGilvray, J. (2012). The Science of Language: Interviews with James McGilvray. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dabrowska, E. (2010). Native v expert intuitions: An empirical study of acceptability judgements. The Linguistic Review, 27, 1-23.

Hyams, N. (1986). Language acquisition and the theory of parameters. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Romberg, A. R., & Saffran, J. R. (2010). Statistical learning and language acquisition Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 1 (6), 906-914 DOI: 10.1002/wcs.78

Tomasello, M. (2000). Acquiring syntax is not what you think. In D. V. M. Bishop & L. B. Leonard (Eds.), Speech and Language Impairments in Children: Causes, Characteristics, Intervention and Outcome (pp. 1-15). Hove, UK: Psychology Press.