Elvis was scheduled to appear on The Steve Allen Show on July 1, 1956, but two weeks before, the variety show host announced that the pressure to cancel the hip-wiggling sensation had been so strong that if Elvis did appear, he "will not be allowed any of his offensive tactics."

Allen, a savvy show business veteran, considered the controversy "a piece of good luck," he said later. All the media hype and attention "worked to our advantage," and Elvis was never really in danger of being canceled.

The host, who was also a comedian, jazz musician, writer, actor, poet, and television pioneer, had tuned in Stage Show one night, where he saw "this tall, gangly, kind of goofy-looking but cute, offbeat kid." He only caught two minutes of him, but "I could see he had something, [and] made a note to our people to 'book that kid.' I didn't even know his name."

Partly to capitalize on the outrage over Elvis's movements on The Milton Berle Show, Allen scratched his head for a different way to spotlight him and also keep his movements contained. As he recalled nearly forty years later, "I personally came up with the two ideas that made Elvis look so good that night -- the singing 'Hound Dog' to an actual dog, and the Range Roundup sketch with Andy Griffith and Imogene Coca," the latter of which was a spoof on the Ozark Jubilee, the Grand Ole Opry, and Elvis's barn dance home, the Louisiana Hayride.

Some of Elvis's fans were offended at the notion of their idol singing to a live basset hound. But Elvis took it all in stride, even agreeing to be fitted for a tuxedo (the twitchy basset would wear a top hat) for the occasion.

At the morning rehearsal on June 29, Elvis became reacquainted with Al Wertheimer, a young photographer only slightly older than Elvis who had photographed him during his fifth Stage Show appearance. RCA's Anne Fulchino had hired the German emigre as part of her dedication to making Elvis a huge pop phenomenon.

With no budget for publicity -- or certainly nothing like the $200 or $300 a day Columbia Records paid freelance shutterbugs -- she'd gone in search of "talented, hungry kids who'd work cheap," striking a deal in which the photographers were free to shop their pictures and make a few bucks once she'd finished her campaign. That's the way she worked with Wertheimer.

She picked him over a temperamental photographer she'd originally considered because Al, a quiet, laid-back, easygoing person, "had the right personality" to shadow the singer in close quarters and a variety of circumstances. "I also knew he could handle the Colonel."

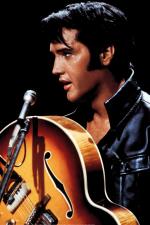

She made the right choice. After late 1956, Parker lowered an iron curtain around Elvis, restricting media access to only a handful of carefully orchestrated events. Before that happened, Wertheimer, a night person like Elvis, would travel with him for a week, shooting some 3,800 frames, all unposed and in natural light, to chronicle both his professional and personal life -- onstage, backstage, in the recording studio, at home with his parents and friends, and on the road with his fans.

No other photographer would capture such startlingly intimate moments or chronicle such an important phase of Elvis's career. The resulting photos, elegant, eloquent, and iconic, "were probably the first and the last look at the day-to-day life of Elvis Presley," Wertheimer has written. "I was a reporter whose pen was a camera."

While RCA needed images that promoted Elvis as an explosive young singer on the rise, Wertheimer had another agenda. "Basically I was covering the story because Elvis made the girls cry, and I couldn't understand what he had that was that powerful, that brought all that raw emotion to the surface."

As Fulchino predicted, Al was so unobtrusive and good at his job that many of the people who surrounded Elvis hardly knew he was there. And Elvis himself enjoyed being documented, allowing closeness that embarrassed even the photographer, particularly for an image Wertheimer calls The Kiss, a brief encounter between Elvis and a fan in the stairway of the Mosque Theatre in Richmond, Virginia.

According to Wertheimer, Diane Keaton, the actress and photographer, has called it "the sexiest picture ever taken in the whole world."

On the afternoon of June 29, after The Steve Allen Show rehearsal, Elvis took the train to Richmond with the Colonel and an entourage that now included his cousins Bobby and Junior Smith, the latter of whom bore the haunted, eerie look of a crazed killer, having come home from Korea with a Section 8. The following day, Elvis was scheduled to perform two shows at the Mosque Theatre, at 5 and 8 p.m.

His date for the day was a well-dressed young woman in a dark, sleeveless dress and cluster pearl earrings. A southern girl, she had a fresh-faced look about her, with her dark blond hair cut in a summer bob. Elvis apparently made her acquaintance in the Hotel Jefferson coffee shop, where only a few minutes earlier, he'd wrapped his arm around the waitress.

He had his script for The Steve Allen Show, and "flipping through some of the pages," as Al remembered, "he was trying to impress this young lady whose name I forgot to get. But she remained cool, not wanting to look too impressed. Elvis continued to try and loosen her up with conversation. At one point, he came in close, within three inches of her face, and just shouted, 'Ahhh!'"

Al clicked off some shots, and then Junior said it was getting late and they needed to go to the theater for rehearsal. Elvis invited the blonde to come along, and a trusting soul, she climbed in the cab. On the ride to the theater, Elvis tried to amuse her, pointing out silly things like light fixtures, and cracking jokes. He "continued to be at turns debonair and playful, or stern," Al observed, "wrapping both hands around her neck in a mock ceremony of choking her."

While the other performers took turns onstage, Elvis flirted with her in another part of the theater, leading her into a dark, narrow alcove along the stairway, lit only by a window and a fifty-watt light bulb. Al, walking from the men's lavatory, which doubled as the musicians' dressing room, was surprised to find the couple there and realized he'd stumbled on an intimate moment. Elvis, dressed in a dark suit and white buck shoes, propped his arm on the stair rail, slouching toward his date, who coyly leaned against the wall. She tipped the lower half of her body, inching toward him, her feet with his, so that the two of them made almost a V-shape standing so close together.

Al was in a quandary. "Do I leave them their privacy or should I be a good reporter? If I shoot this, Elvis may have me fired." Then he took the chance, seeing they were so absorbed. He started shooting, keeping his distance at first, and then moved closer, closer, and closer still, until he was up on the railing of the stairway. He snapped a shot from above, looking down just as Elvis nuzzled the girl's cheek, his arms spread wide, one above her against the wall, the other anchoring him on the railing. It was so sensual, and their bodies so eager, that if the photo were rotated, it would seem as if the two were in bed.

The photographer scarcely breathed. He asked to pass them ("May I get by?"), but they were so focused they didn't even care. Al pivoted so that the window was behind him, illuminating his subjects with front-end sunlight and fill lighting from the dangling bulb.

"Betcha can't kiss me, Elvis," the girl said, sticking out her tongue.

"Betcha I can," he teased back. And then he made his move, sticking out his own tongue until the two were pressed together, tongues and noses, his waist pushing up against hers. By now, the girl was leaning back on the stair rail, and anything could happen. Al snapped the shutter, capturing the famous image, a distillation of the rock-and-roll road show, and Elvis at his uninhibited best.

The whole thing took a tenth of a second, and then all Al heard was, "We want Elvis! We want Elvis!" A minute later, Elvis sprinted onstage to give four thousand people, mostly women and girls, the performance they had paid to see.

Just who Elvis's date was that day remains a mystery. Since the image appears on commercial products, several women have approached Wertheimer through the years, each insisting she was the one. But whenever the photographer asks them questions about the day before or the day after, their stories never gel. "I think Elvis kissed thousands of girls. He loved kissing girls."

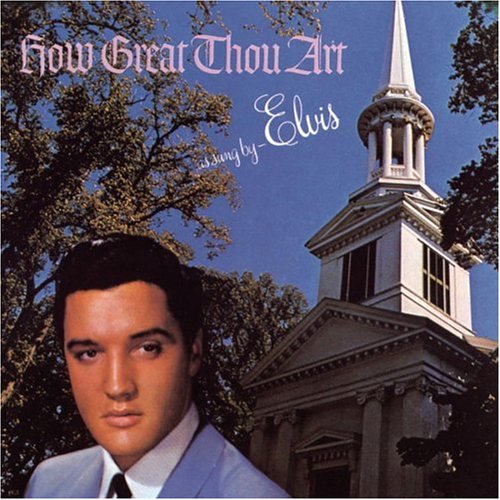

After his shows that night, Elvis climbed back on board a northbound train -- flying scared him -- for his live appearance with Steve Allen the next evening. It was a Sunday. The show went as planned, Elvis wearing his prom-night blue suede shoes with his tuxedo and performing "I Want You, I Need You, I Love You" along with "Hound Dog."

He would record the latter song the next day at the RCA studios on New York's East Twenty-fourth Street, along with "Don't Be Cruel" and "Any Way You Want Me." Meticulous at getting what he wanted on tape, though, as in his Sun [Records] days, still arriving unprepared, Elvis took control of the recording session. ("Try a little more space," he told Scotty at one point.) After several takes of "Don't Be Cruel," he squatted on the floor so his ears were at the same level as the huge speakers in the corner. No, he said. They would need to do it again.

By the end of the day, he had insisted on twenty-eight takes of "Don't Be Cruel," and thirty-one of "Hound Dog." It was excessive, but no one was going to argue with him, because he was an idiot savant in the studio, knowing what would work, even if he couldn't always articulate it quickly. Beforehand, he'd spoken again to the press, saying that "Barbara Hearn of Memphis and June Juanico of Biloxi, Mississippi," were the two girls he dated, Barbara being a good motorcycle date, he threw in. Meanwhile, outside the RCA building, fans held up signs saying, WE WANT THE REAL ELVIS, and WE WANT THE GYRATIN' ELVIS, not the restrained and sanitized one who appeared on The Steve Allen Show.

But New Yorkers had seen two very different aspects of Elvis's personality in an exceedingly short time. At eleven-thirty that Sunday night, little more than three hours after the Allen show signed on, Elvis appeared live on the WRCA-TV interview program, Hy Gardner Calling! Gardner, a popular syndicated newspaper columnist, asked his guest the increasingly familiar questions about his critics, his music, and his effect on teenagers. Elvis, on camera at the Warwick Hotel, but holding a telephone to speak with Gardner, took it in good humor, answering a question about his four Cadillacs ("I'm planning for seven") as well as a ridiculous rumor that he had once shot his mother. ("Well, I think that one takes the cake. That's about the funniest one I've ever heard.")

The show was memorable for two reasons -- the shot of Elvis on the telephone exposed an ugly and prominent wart on his right wrist, which he would have removed in 1958. (A Georgia fan named Joni Mabe would acquire it and keep it in a jar of formaldehyde, selling T-shirts proclaiming, THE KING IS GONE, BUT THE WART LIVES ON.) What got people talking, though, was Elvis's sleepy eyes and druggy speech.

Two weeks earlier, he had stopped by Wink Martindale's WHBQ-TV "Top 10 Dance Party" to promote his upcoming concert at Memphis's Russwood Stadium, a charity benefit for the Press-Scimitar's Cynthia Milk Fund, and his behavior on the show had also seemed somehow altered. He stuttered more than usual and was nervous in the company of the kids in the studio that afternoon. Then, with a lock of hair meandering on his forehead, he leaned on the jukebox for most of his brief interview, and nearly fell off of it when he went to shake Wink's hand. Elvis had initially resisted coming on the show, saying he didn't feel comfortable doing a live interview, even on local TV. Wink asked Dewey Phillips to speak with him about it, and then Elvis agreed, but only if Dewey appeared with him on camera. Had Dewey, who used Benzedrine to keep himself awake and sedatives to bring himself down, plied Elvis with pills?

Wink later tried to explain it away as growing pains.

"He was very awkward in that era. He didn't seem to know how to act around people. He just didn't know how to be interviewed at that stage of his career."

And maybe that was part of it, along with sleep deprivation. He told Hy Gardner he slept only four or five hours a night, but some of the audience thought it was more than that. Hy apparently did, too, saying, "Several newspaper stories hinted that you smoked marijuana ... in order to work yourself into a frenzy while singing." ("Well, I don't know," Elvis replied with a laugh.) In 1956, drug use was mostly relegated to the underground, to bowery dwellers, jazz musicians, and the criminally insane, and mainstream America found it both horrifying and scandalous. In billboarding the guests on the show, Gardner's secretary, Marilyn, announced, "We'll talk with veteran bandleader Ted Lewis; Egyptian dancer Nedula Ace; and the unidentified author of the shocking book titled I Was a Dope Addict. And to get right into action immediately with the most controversial entertainer of the year ... well, you'll hear who."

On July 3, Elvis took a cab to New York's Pennsylvania Station and once more boarded a train, this time for a twenty-seven-hour trip to Memphis. There he would enjoy a few hours of Fourth of July celebration with his parents, cousins Junior, Bobby, and Billy Smith, his aunt and uncle Travis and Lorraine Smith, his Memphis girlfriend, Barbara Hearn, and a growing entourage that now included Red West and an overgrown Memphis boy named Arthur Hooten, whose mother had worked with Gladys at Britling's Cafeteria. On the train, he listened to the quick-cut acetates of his three new songs on a portable record player, second-guessing himself, rethinking his vocals, wondering if his voice was too out front from the instruments.

When the coach arrived in Memphis, it slowed just long enough for Elvis to disembark at a small signal stop called White Station. From there, the star of Sunday night's Steve Allen Show and Hy Gardner Calling! walked home to Audubon Drive with his alcoholic and perpetually shell-shocked cousin Junior. Everybody wondered how he'd do with the fireworks that night, since Junior, a wild and unpredictable personality, had gone berserk and shot a group of civilians in a Korean village.

As usual, the yard was abuzz with fans, who normally contained themselves to the carport, except when Gladys or Vernon invited them inside, which the Presleys did quite frequently, accepting them with calm resolve. The house was especially active on this day, however, and not just for the holiday. A number of fans had traveled to Memphis for Elvis's Russwood Stadium show that night, some of them getting up the nerve to come see where he lived.

Vernon was already in something of a state when Elvis walked in. The family had just had a swimming pool installed in the backyard, but the pool wouldn't fill. Now Vernon was running a hose from the kitchen sink. Elvis hurried to put on his trunks, and then jumped into all of three feet of water, horse playing with his cousins for Al's camera.

Inside, Barbara, dressed for the evening event, sat in a taffeta, scoop-neck black-on-white polka-dot dress. Like the girl in Richmond, she, too, wore cluster pearl earrings, with a smart pair of black pumps setting it all off. She waited for Elvis to take his shower, and then half-naked, clad only in his pants and socks, his hair still tousled, he beckoned her into the living room to hear his acetates.

Minnie Mae [Elvis's grandmother] sat on the couch, craning her neck forward, trying to make out the words to "Don't Be Cruel." But Elvis wanted to know what Barbara thought of all the songs, wanted her compliments and reassurance that he would have a hit. In the end, he needn't have worried. The double-sided single, "Hound Dog/Don't Be Cruel," sat at the top of the charts for three months and became the most-played jukebox record of the year.

They made an odd pair, Elvis and Barbara. Al Wertheimer, taking note, found her to be "a model of gentility ... pert, prim, and polite" as a schoolmistress, while Elvis, shirtless, with boils on his back, "looked like the unruly student who spent most of his time leering at the teacher." She sat next to Minnie Mae for a while, just on the edge of the couch, holding her purse on her knees.

"Let's dance," Elvis said. But Barbara didn't want to dance. "No, not now," she answered. She was concentrating hard on the music. But Elvis persisted, pulling her to her feet and then hugging her, moving in for a kiss. Barbara complied, but "I didn't want him to be kissing me in front of his grandmother."

Minnie Mae took the hint, saying she had to get ready for the concert that night. Elvis took Barbara's hand again, and they began dancing in the narrow space between the coffee table and the couch. Her heart wasn't in it, though, and Elvis could tell. Finally she said she just wanted to listen.

"He shrugged, plopped down on the plush chair and sulked," Wertheimer wrote in his book, Elvis '56: In the Beginning. "She sat on the edge of the ottoman next to the hi-fi, picked at her pearl-clustered earrings and stared at the carpet. Elvis stared at her, clamped his lips in a pout and glared at a different patch of the carpet. His record filled the room, 'Don't make me feel this way/Come on over here and love me ... .'

"'How do you like it?'" he asked.

"'I think it's very good,' she said. She liked all of his music except for 'Old Shep.'"

Then he asked if she wanted to hear the new ballad, "Any Way You Want Me." She stood, and Elvis folded his arms around her and pulled her to his bare chest. It was an awkward embrace -- she was shy with Al there -- and Wertheimer knew it was time to explore the rest of the house.

That night Elvis, dressed entirely in black, rode in a police car to nearby Russwood Stadium. Barbara sat with Vernon and Gladys, Minnie Mae, and Elvis's aunt and uncle in a VIP section near the stage. The hometown fans, so proud to have seen him on The Steve Allen Show, were already on their feet in the dilapidated old baseball park, and the noise was deafening as Elvis took the stage. "You know those people in New York aren't going to change me none," Elvis told them. "I'm gonna show you what the real Elvis is like tonight."

It was a sentimental and emotional evening all around. Elvis saluted his family from the edge of the stage. And Bob and Helen Neal had come back afterward, bringing their new employee, Carolyn Bradshaw, Elvis's little sweetheart from the Hayride. She and Elvis had never really said good-bye, and now he spotted her. They waved and started toward each other, but it was not to be.

"We didn't get to say anything, because all of a sudden, he was just inundated with people. I don't know where all these people came from, but it looked like he'd never get away, so I just gave up and went on home. That was the last time I ever saw him."

Sitting just a few rows from the stage that night was another young girl with stars in her eyes, this one just at the beginning of her relationship with Elvis. Jackie Rowland, the 190-pound "blueberry" from the Jacksonville, Florida, show, had made good on her promise to lose weight, and even though "my mother kept me almost in a bubble," Marguerite had held up her end of the bargain, too, bringing Jackie, now fourteen years old and eighty pounds lighter, to Memphis.

They arrived at the Audubon Drive house on July 3 while Elvis was still in New York. Vernon saw them standing on the sidewalk, watching all the fans milling about, and came out and struck up a conversation. Marguerite explained how they happened to be there, and that Jackie had worked so hard to lose her weight, and just wanted to see Elvis so much. Vernon listened sympathetically.

"He said if Mrs. Presley would let us in, he would come to the side door, and that's what happened," Jackie vividly recalls.

Gladys, whose own weight continued to balloon, liked the personable mother-daughter, even inviting them to spend the night. They politely declined -- they had a motel already -- but said they would like to come back the next day, when Elvis was home. So on the Fourth of July, in the afternoon, before the Russwood show, the Rowlands returned to the house to visit.

The five of them -- Elvis, his parents, and the Rowlands -- sat in the living room, Gladys already in her dress for the concert. While Elvis sat between his parents on the couch, intently reading a story about himself in the newspaper, Jackie snapped his picture. Then Vernon scooted over, seeming even more the outsider, and Jackie sat down beside her idol, who draped his arm around her and held her close, his mouth so near her ear.

Jackie's mother captured the moment in a snapshot. But Elvis does not appear to be a pop star greeting a fan he had met only briefly once before. Instead, both Jackie and Elvis look as natural and relaxed as if they were longtime sweethearts. Though Jackie was an only child "and I had never had a boyfriend and the only males that came near me were my family," neither she nor Elvis seem self-conscious at being so physically affectionate in the presence of their parents. Elvis had a way of putting people at ease, but this was extraordinary.

Yet Jackie says it was not precisely as it seemed.

"I think one of the reasons Elvis and his mother liked me was due to my reaction to his first attempt to kiss me. I was totally innocent and naive. I told him to stop it and pushed him away. You can see by my expression in the photo."

Though Elvis was told no, it didn't faze or deter him. "He didn't care, he just put his arm around me again and started nibbling my ears." In a lighthearted tone, "He told my mother she needed to take me to a doctor because I wasn't normal. I'm sure he had never met a girl who wasn't all over him."

Elvis demanded complete control in his relationships, but perhaps another reason he persisted was because Jackie looked a bit like him. Their hair color was the same, they had those light eyes, and they were the only surviving children of their parents, their mothers both having lost a baby at birth. For a brief moment, it might have seemed like Jessie and Elvis, reunited. Even Jackie's name, like June's, started with the right letter.

By the time Jackie left the house, "There was definitely some romantic chemistry going on between the two of us. I didn't think about Elvis being a big, famous entertainer. He was just the sweet boy that I was in love with."

Of course, her familiarity with the family had begun the day before. Gladys admired a stick rhinestone pin that Marguerite wore, and Mrs. Rowland "sold" it to her for a penny, and then showed Gladys how to store a set of sterling silverware Elvis had just bought her. After that, Gladys led Jackie through the house. "I took pictures of Elvis's bedroom, his clothes closet, his messy bathroom -- anything that a little fourteen-year-old girl would think to do."

However, twenty-one-year-old Elvis did not treat Jackie as the child she was. He sang his new song, "Hound Dog," and started tickling her ("You know how boys love to tease and pinch girls"), calling her Goosey. From there, it grew more intense. "He said, 'You've got the most beautiful eyes I've ever seen,' and he was really tickling me, kissing me on the cheek and the ears. Something just clicked between us, and that was it."

Gladys, already guessing how Elvis would react to Jackie, had taken her alone that first day, auditioning her, as she did the older girls in whom Elvis took an interest. "She sat me down and asked me if I had a boyfriend, and what kind of grades I made in school, and did I believe in Jesus. She really asked me very personal questions, but, of course, at the time, I didn't think those were personal questions. I answered them, and I was happy to answer them, because I was proud of what I'd done in school and in my church."

Even at fourteen, Jackie had the sense that she was being interviewed to see if she measured up. It was almost as if Gladys were screening Jackie in an attempt to find a younger version of herself for her son. And Gladys was direct with her about her competition.

"She knew about the 'traveling girls,' as I call them, and she explained to me that Elvis hadn't sown all of his wild oats yet. It didn't bother me, because she said I still had time to grow up."

In fact, when Jackie returned to Jacksonville, she was convinced that she would see Elvis again soon, and that he wanted it as much as she did.

In a few weeks, an envelope arrived at Jackie's home. Elvis, who wrote few letters, had invited her and her mother to his show at Jacksonville's Florida Theater the following month. "This letter was written to Mrs. Rowland and Jackie, and it's signed with Mrs. Presley's name. But it's Elvis's handwriting. He started to sign his own name, but he knew that was improper. You just didn't do things with an underage girl."

The day after the Russwood concert, Elvis gave himself a well-earned three-week vacation. It was his first real time off since becoming a national sensation. He'd always had trouble sleeping, and now sleep sometimes seemed forever out of reach, his foot just going all the time under the sheets.

He drove down to Tupelo on July 7, and then two days later showed up unexpectedly at June Juanico's door in Biloxi, with Red West, Gene and Junior Smith, and Arthur Hooten in tow. He was living in the moment now, not really planning much of anything, except to hang with his pals, maybe do a little fishing, a little sightseeing. He put the whole party up at the Sun 'N' Sand Hotel Court, and then moved to a villa at the Gulf Hills Dude Ranch resort in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. But after fans keyed messages into the paint of his new car, he rented a private home.

June was walking down Howard Avenue when he arrived, never dreaming he was anywhere near. "There was a group of girls coming up the street, and they saw me and said, 'June! Elvis Presley's at your house!' Boy, I took off at a fast pace to go and see."

When she got home, there was no sign of him, only a clutch of schoolgirls in her yard. Her mother, May, told her he'd been there, and that he was really ticked because he didn't have any privacy. He'd left a message for her to call the Sun 'N' Sand. The whole town seemed to be on the phone, though, and when she finally got through, Elvis gave her grief about it: "You told everybody in Biloxi I was coming!" She tossed it right back: "I didn't even know you were coming! You arrive in a white Cadillac convertible with a Memphis tag and your sideburns flapping in the wind? C'mon!"

Elvis's presence escalated the rumor flying around Biloxi that he and June were engaged. A New Orleans radio station, WNOE, picked up on it, reporting it on the air, which sent the Colonel into orbit. Parker ordered Elvis to drive to New Orleans immediately and deny it. Unannounced, Elvis walked into the station and did an on-air interview.

"Elvis, how are you?" the interviewer began.

"Fine. How are you, sir?"

"Wonderful. When did you come into town?"

"Well I just came in a few minutes ago."

"You drove up from ... "

"A few minutes ago. [Laughs] Yeah, I was in Biloxi and I heard on the radio where I was supposed to be engaged to somebody, so I came down here to see who I was supposed to be engaged to." [Laughs]

"Well, just what is the story? Are you engaged to anybody?"

"The girl they were talkin' about, June Juanico, I've dated a couple times."

"Are you ... "

"We're not engaged."

"Are you serious about anybody?"

"I'm serious about my career right now."

The interviewer gave it a rest, asked about his next release and his career, and then put him in the hot seat again.

"How old are you, Elvis?"

"Twenty-one."

"What age do you think might be the best for you to get married?"

"I never thought much about it. In fact, I have never thought of marriage ... I'll say this much, I'm not thinkin' of it right now, but if I were to decide to get married at all, it wouldn't be a secret. I mean, I'd let everybody know about it. But I have no plans for marriage. I have no specific loves. And I'm not engaged, and I'm not goin' steady with nobody or nothin' like that."

"Well, you know how this whole thing started last night. We got -- "

"Excuse me for buttin' in, but I don't know how it got started, but everywhere I go, I mean, I'm either engaged or married, or I've got four or five kids or somethin' like that."

"But you're not."

"Everywhere I go. Nah."

"You're as free as the breeze."

"That's right."

Elvis's interviewer then tried to move on.

"Well, Elvis, thank you so very much again, and we wish you lots and lots of good luck in your continued meteoric rise to stardom. ..."

"Thank you very much. I've enjoyed talkin' to you, and I hope that we got the little rumor cleared up, because it's just a rumor and nothin' more. If it wasn't, then I wouldn't care for tellin' anybody. I wouldn't be ashamed of it."

"Why don't you say it just one more time, so people still don't get the wrong idea?"

[Laughs] "Well, I'm not engaged, if that's what it's supposed to be."

He got the heck out of there then, and he and June and the gang went to the Pontchartrain Beach Amusement Park to blow off a little steam before heading back to Biloxi. The next morning, June awakened to a phone call from a reporter from the New Orleans Item. "Did I kiss him good night? What do you think? He's wonderful!"

A day or so later, they went deep-sea fishing on the boat the Aunt Jennie with June's mother and her boyfriend, Eddie Bellman. Elvis looked out at the blue water and thought about his upcoming tour of Florida. He still wished he could take his parents to see the ocean, but maybe he could get them to come down to Biloxi now. That way, he could stay down longer with June, too, and not have to worry Gladys. To his surprise, Gladys and Vernon said yes, and the Presleys arrived on Friday, July 13, staying the weekend. Elvis and June took them out on the Aunt Jennie, and then to New Orleans to see the sights before they returned to Memphis. When they parted, Elvis embraced his mother.

"She would just dig into him," June noticed. "You could see tears well up in her eyes anytime she left him. His daddy came around the door where his mama was getting in, and he was shaking his daddy's hand. But Vernon was not really that affectionate, not like she was."

Elvis was back in Memphis by July 20, but apparently lovesick, he returned to Biloxi nine days later. He'd talked it over with his mother, and contrary to what he'd told WNOE Radio only ten days earlier, he was serious enough about June to think about marriage. But he wanted her to wait three years. "He said, 'I can't get married right away. I promised the Colonel I wouldn't do anything that would affect my career. Will you wait for me?'"

June hated the "nuisance" of his fame -- it was getting so that if they wanted to do anything, they had to wait until the middle of the night to go out so he wouldn't be mobbed. But she was "crazy insane about Elvis," so she said yes,